Signal or Noise? The Network Museum

Art, Technology and Culture Colloquium

February 16, 2000

Thank you Ken for inviting me here tonight. It is a great pleasure to speak in such a distinguished series as the Art, Technology and Culture Colloquium.

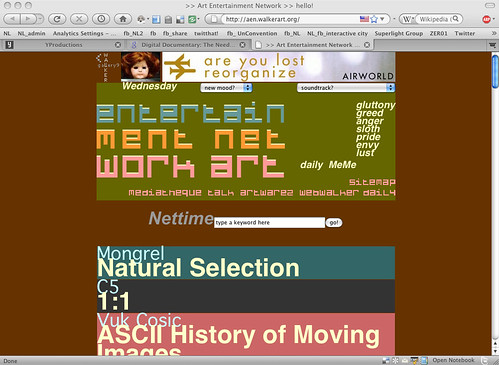

What I would like to talk about tonight are some of the issues surrounding brick and mortar museums in a network environment, particularly in terms of net art. It will necessarily be incomplete, but I hope it will shed some light - for me as much as for you, perhaps - on a project I have been working on for the past year, which opened last Friday, Art Entertainment Network.

First, I would like to give you some brief background about the Walker Art Center, where I [used to] work.

Center and Museum

The Walker is not a museum but a center whose mission is to be a catalyst for creative expression and the active engagement of audiences. Its mission is different than, say, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum where I worked previously, and we very self-consciously did not want to show the work of any artists whose reputation was not already established. It was not about supporting the creation of art but about supporting its context, I suppose you could say--the creation and diffusion of knowledge.

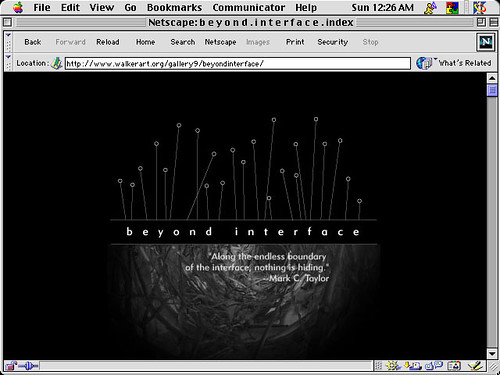

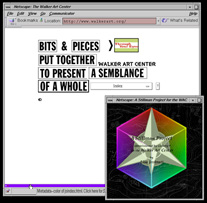

The Walker is the official second home for choreographer and dancer Bill T. Jones, has co-produced film works by Lorna Simpson, Sadie Bennig, and Matthew Barney, and has sponsored dozens of artist residencies over the years from Mark Luyten to Rikrit Tiravanija to Sue Coe, 3 new web works by emerging artists for Gallery 9, which we recently received continued funding from the Jerome Foundation to commission. In other words, it is part of the institutional fabric to support what Gerfried Stocker, the artistic director, of Ars Electronica and its "Museum of the Future" has called the necessary move from the exhibition of finished products to being a platform supporting a global exchange of views and artistic production.

The Walker is not alone in what they do, of course, and I certainly do not mean to be setting up any artificial debates between "museums" and "centers." Many museums, including here in the Bay Area, SFMOMA and the Berkeley Art Museum among others, maintain an active commitment to contemporary art, while "centers" whether the Walker, or the SF Art Institute or CCAC, are not exempt from Tom Sherman's skewering observation:

"Death, in particular the death of creative people, plays such a fundamental role in societal development. The flowering of cultural prestige through the accrual of death is absolutely phenomenal if the accomplishments of the deceased are well documented and promoted aggressively. This is why information technologies and communications media have been able to take their place alongside traditional cultural institutions."

net art and Art on the Net

However, I do want to try and draw a distinction tonight between what I and many others have called net art and Art on the Net.

net art is jodi and irational and vuk and easylife. net art is Homework and Bodies Inc. and Tillie and SoftSub and Summons to Surrender and Dislocation of Intimacy. net art is the projects in the Walker's Gallery 9, Dia and MOMA's "web projects," the Guggenheim's CyberAtlas, ZKM's net_condition., Ars Electronica's annual prize, and , presumably, SFMOMA's new eSpace and $50,0000 Webbys.

There are purists and not-so-purists in regard to net art, and presumably this will be part of what is debated over the next 3 days in the CRASH symposium--as well as, I should add, at the Walker's international conference in April, "Sins of Change: Media Arts in Transition, Again," which we are sponsoring along with the Kitchen.

But net art is different than documentation of Art on the Net. The over 70,000 images of works of art in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco's Imagebase are a fabulous resource and the Thinker, as it was called, was a real kick-in-the-pants from Dakin Hart and cohorts for the rest of the cultural heritage community. Thank you Dakin.

The Walker's and The Minneapolis Institute of Art's award-winning collaboration ArtsConnectEd is a fabulous education-oriented front end on an impressive database, which also raises interesting critical and philosophical questions about what the museum is in the network age. But these efforts are not net art.

I'm sure this seems obvious to most of you in the audience, but I think it is surprising how often discussions about art, artists, museums, the network, technology, etc. confuse and conflate the museum as archive and the network as delivery system with the institution as catalyst, the network as medium. Part of the reason for this, of course, is that the distinctions are not as neat and tidy as I am suggesting. I do know this. But for now, let me pose a question.

We know intuitively/obviously/automatically that there is a clear difference between say Piotr Szyhalski's Ding an sich: The Canon Series commissioned by the Walker's Gallery 9 and an image of Claes Oldenberg's Three-Way Plug from the Walker's permanent collection--no matter how informatively we try to contextualize it. I should also add that I hope we know that there is a clear similarity. Both are works of art.

As a sidebar, I think it is important to recognize that there is a general problem with terminology. At the very least, terms such as "new media" guarantee that we new media practitioners will be old and presumably tired media practitioners in a matter of days. In terms of net art, we don't want to box artists into formalist categories. I am more interested in hybridity than purity. I am as interested in the net itself as a work of art as a space for net.artworks.

The network is profoundly transforming, but that does not mean our grandchildren will recognize our stories about good old "www" anymore than we can understand the contents of a telegraph codec. Net art, for me, is profoundly engaging and challenging, but this does not mean that we have come to the end of some road, where everything will be digital and on the network or be unknown and unseen.

There Is No There There

On the other hand, just because the network may not prove to match exactly the FUTURE AS FORTOLD BY WIRED, doesn't mean it won't change everything. Although, admittedly I sometimes ask myself, "Everything except museums?"

"In all the arts there is a physical component which can no longer be considered or treated as it used to be, which cannot remain unaffected by our modern knowledge and power. For the last twenty years neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial. We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art."

Yet, we still seem to have difficulty thinking about the network museum in a way parallel to how we are finally coming to understand network-based art. As different. As the same. As real.

Of course, the network museum is not destined. After all, we don't expect museum catalogs to be museums. But that is precisely the point. In his wonderful and still-wise essay, "Other Criteria," Leo Steinberg wrote:

"[the flatbed picture plane] is no more than a symptom of changes which go far beyond questions of picture planes, or of painting as such. It is part of a shakeup which contaminates all purified categories. The deepening inroads of art into non-art continue to alienate the connoisseur as art defects and departs into strange territories leaving the old stand-by criteria to rule an eroding plain."

From the evidence of exhibitions such as Let' Entertain and Art Entertainment Network, currently on view at the Walker, art certainly is and has been for some time defecting into strange new territories--one of them being the net. Unless we are content to simply kick around in that eroding plain of "museum-quality art," I would argue that the "network museum" is as necessary--for museums--as the rise of museums of modern art, alternative spaces, screening spaces, performing spaces, etc. Whether the network museum can be of any use to the artist remains to be seen.

Transmitting the Signal: Information, Redundancy, Noise

One of the truisms of the digital age is that information at your fingertips does not necessarily lead to enlightenment. Museums are remarkable repositories of facts and information, but the promise of the digital networks seems often to result in a Babel of knowledge. As Hal Foster has warned in "The Archive without Museums," One of the truisms of the digital age is that information at your fingertips does not necessarily lead to enlightenment. Museums are remarkable repositories of facts and information, but the promise of the digital networks seems often to result in a Babel of knowledge. As Hal Foster has warned in "The Archive without Museums,"

"If, according to Malraux, the museum guarantees the status of art and photographic reproduction permits the affinities of style, what might a digital recording underwrite? Art as image-text, as info-pixel? An archive without museums? If so, will this database be more than a base of data, a repository of the given?"

Without getting into issues of meaning, yet, I would like to explore one of the canonical texts of information theory, Claude Shannon's 1948 treatise, "The Mathematical Theory of Communication, which, according to Scientific American,

"Before this there was no universal way of measuring the complexities of measuring the complexities of messages or the capabilities of circuits to transmit them."

Mathematical measurement, of course, is abhorrent in the arts. How can you quantify the quality of an experience? How can you compute aesthetics? On the other hand, aspects of Shannon's theories are intriguing, even if only at the metaphorical level.

First, to crudely describe Shannon's theory, he created a mathematical metric by which to measure information, with some of the key terms being information source, redundancy, and noise, the interaction with which what we now call a codec--a coding and decoding algorithm - determined the strength of the signal. I am sure Ken, wearing his engineer hat, will correct me in the questions and answers, but indulge me for now.

Information

According to the theory, information is measured as a function of how much a message tells you what you did not know prior to receiving the message - in other words, as ignorance-reduction. To use the slightly archaic example of a father standing outside the window of a maternity ward at the hospital, who does not know the gender of his child, he has two possible choices. If the nurse signals to him that it is a girl, two choices become one. His prior uncertainty is halved. This equals one bit of information, regardless whether it is conveyed via a pre-arranged signal such as one finger for a boy, two for a girl, or if the nurse were to come out and say to the father, "Congratulations. You must be very proud. I'm delighted to be the first to tell you that your child is a girl." According to the theory, information is measured as a function of how much a message tells you what you did not know prior to receiving the message - in other words, as ignorance-reduction. To use the slightly archaic example of a father standing outside the window of a maternity ward at the hospital, who does not know the gender of his child, he has two possible choices. If the nurse signals to him that it is a girl, two choices become one. His prior uncertainty is halved. This equals one bit of information, regardless whether it is conveyed via a pre-arranged signal such as one finger for a boy, two for a girl, or if the nurse were to come out and say to the father, "Congratulations. You must be very proud. I'm delighted to be the first to tell you that your child is a girl."

This is all well and good, but what is a bit startling is how Shannon and others describe information as only being information if it surprises the recipient. According to the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins,

"'It rained in Oxford every day this week,' carries little information, because the receiver is not surprised by it. On the other hand, 'It rained in the Sahara desert every day this week' would be a message with high information content. . . . Shannon wanted to capture this sense of information content as 'surprise value.' It is related to the other sense--'that which is not duplicated in other parts of the message' - because repetitions lose their power to surprise."

Or as the AI researcher Roger Schank puts it more succinctly - but it is still the same number of bits of information: "Information is surprises. We all expect the world to work out in certain ways, but when it does, we're bored."

To my mind, part of the issue of museums and net art is that a links list, which is so often what we end up with, carries very little in the way of surprise - a surprise that can be truly astonishing when you fall into an artist's site. This is another way of saying that the museum is not a source of information, so we're bored.

Redundancy

Repetition is not necessarily all bad. Redundancy, as Shannon called it, is defined simply as the inverse of information. In common usage, the word redundancy clearly has negative connotations. It is perhaps redundant of me to even state this. On the other hand, redundancy has its value. If, for instance, there is an error in transmission, unless there is some redundancy, it is impossible to reconstruct the message with any degree of certainty.

Or, to use another example from Dawkins, Repetition is not necessarily all bad. Redundancy, as Shannon called it, is defined simply as the inverse of information. In common usage, the word redundancy clearly has negative connotations. It is perhaps redundant of me to even state this. On the other hand, redundancy has its value. If, for instance, there is an error in transmission, unless there is some redundancy, it is impossible to reconstruct the message with any degree of certainty.

Or, to use another example from Dawkins,

"'Arr JFK Fri pm pls mt BA Cncrd flt' carries the same information as the much longer, but more redundant, 'I'll be arriving at John F. Kennedy airport on Friday evening, please meet the British Airways Concorde flight.' Obviously, the brief telegraphic message is cheaper to send (although the recipient may have to work harder to decipher it - redundancy has its virtues if we forget economics.)"

Perhaps an museum archive/collection of net art, though redundant, has similar value - the ability to reconstruct ephemeral events - and virtue - a more prolix iteration for the uninitiated. Perhaps.

Noise

The other variable in the "surprise" equation is noise. According to Warren Weaver, with whom Shannon co-authored a 1963 preface to his 1948 text, The other variable in the "surprise" equation is noise. According to Warren Weaver, with whom Shannon co-authored a 1963 preface to his 1948 text,

"In the process of being transmitted, it is unfortunately characteristic that certain things are added to the signal which were not intended by the information source. These unwanted additions may be distortions of sound (in telephony, for example) or static (in radio), or distortions in shape or shading of picture (television), or errors in transmission (telegraphy for facsimile), etc. All of these changes in the transmitted signal are called noise."

I think many artists believe that most museums' efforts related to net art - where they even exist - are often just noise, distorting the signal - the direct, one-to-many relationships that any artist can have with anyone with an Internet connection.

It may be that in Shannon's model all the interpretive stuff is a kind of noise, confusing the signal, and what is critical is the elegance, speed, and accuracy of the algorithm used to encode and de-encode the information source and transmit its signal. The museum as codec. How would that work? According to Weaver and Shannon,

"The best transmitter, in fact, is that which codes the message in such a way that the signal has just those optimum statistical characteristics which are best suited to the channel to be used - which in fact maximize the signal . . . entropy and make it equal to the capacity C of the channel."

Got that? Basically, as I understand it, the best transmitter is a question of efficiency, which is greatly enhanced by paying attention to the characteristics best suited to the channel. And while it may or may not prove true in the end that the museum is a good transmitter of artistic practice, certainly, as a transmitter of its own signal, it is important that the museum optimize for the network, if that is a channel it is interested in.

Lines of flight

Noise, of course, as we have learned from John Cage and others, is just be another way of listening, of engaging.

In a wonderfully poetic posting to the voti listserv last year, "The Ante-Chamber of Revolution: A Prelude to a Theory of Resistance and Maps," Ricardo Dominguez, one of the principals of Electronic Disturbance Theater, wrote:

"Several different maps of information have been put on the block for our inspection: frontier, castle, real estate, rhizome, hive, matrix, virus, network,"

and he invites us to "plug in" our own map, saying:

"Each map creates a different line of flight, a different form of security, and a different pocket of resistance."

This vision of a "different line of flight" echoes a statement by Manuel DeLanda in an interview with Brett Stallbaum in Switch. He said:

"The artist is that agent (human or not) that takes stratified matter-energy or sedimented cultural materials, and makes them follow a line of flight, or a line of song, or of color."

The point about looking at Shannon's ideas regarding the Mathematical Theory of Communication is not as a literal blueprint. It is more metaphorical. And pragmatically speaking, while it seem inescapable to follow Marshall McLuhan's dictum that, initially, we tend to understand any new medium in terms of preceding media, I think it is interesting to try and think of the network museum in network terms more than in terms of art history - or probably I should say as well as in terms of art history.

Some Possible Distinctive Characteristics of the "Network Museum"

David Antin's seminal essay, "The Distinctive Features of the Medium" was about video, but substitute the work net, and you have a relevant and cogent analysis:

"Net art. The name is equivocal. A good name. It leaves open all the questions and asks them anyway. Is this an art form, a new genre? An anthology of valued activity conducted in a particular arena defined by display on a computer monitor? The kind of net activity made by a special class of people--artists--whose works are exhibited primarily in what is called "the art world" - ARTISTS' NET ACTIVITY? An inspection of the names in the online catalog gives the easy and not quite sufficient answer that it is this last we are considering, ARTISTS' NET ACTIVITY. But is this a class apart? Artists have been making net pieces for scarcely ten years--if we disregard one or two flimsy hacker jobs and Ivan Sutherland's 1962 "Sketchpad" - and net activity has been a fact of gallery life for barely 5 years Yet we've already had group exhibitions, panels, symposia, magazine issues devoted to this phenomenon, for the very good reasons that more and more artists are using the net and some of the best work being done in the art world is being done on the net. Which is why a discourse has already arisen to greet it. Actually two discourses: one, a kind of enthusiastic welcoming prose peppered with fragments of communication theory and McLuhanesque media talk; the other, a rather nervous attempt to locate the "unique properties of the medium." Discourse 1 could be called "cyberscat" [!] and Discourse 2, because it engages the issues that pass for "formalism" in the art world, could be called "the formalist rap." [emphasized words substitutions]

What I'd like to do in the rest of my talk is blue-sky about a "network museum" that has information value - in other words, that may be surprising. Rather than a straight-line augmentation of the given - how can we email our calendar? How can we sell tickets online? Let's make pictures of our collection viewable online - what might the "network museum" look like if it took its cues from the specificities of the network, particularly as articulated in the lines of flight of artists?

Multiplicity of Choice: "Captivate and Transport Me"

According to Shannon, the more choices there are, the more information there is.

"Information is a measure of one's freedom of choice when one selects a message. . . . If all choices are equally likely, the more choices there are, the larger H will be. There is more 'information' if you select freely out of a set of fifty standard messages, than if you select freely out of a set of twenty-five."

Just as one can marshall Shannon's theory to question whether the critical intervention of the museum boosts the signal of the artist information source or interferes with it like static, this idea of information being related to the quantity of free choice runs counter to one of the affirmations we chant to ourselves in the mirror in the morning:

They'll always need a filter. There is too much to choose from. Too much information. They'll always need filters. Amen

But does the museum, by defining one of is roles as being a filter, a kind of girdle for too many choices, risk becoming irrelevant to this particular channel - the network? It is true, according to Shannon and Weaver, that

"The greater this freedom of choice, and hence the greater the information, the greater is the uncertainty that the message actually selected is some particular one." But they continue, "Uncertainty which arises by virtue of freedom of choice on the part of the sender is desirable uncertainty. Uncertainty which arises because of errors or because of the influence of noise is undesirable uncertainty."

Here is a bit of a conundrum. We promote the virtue of information. The more the better. Yet this can also increase the uncertainty of whether any particular message is being received.

From a content perspective, it makes sense to limit information choices to those that relate to your topic - a shoe museum, an exhibition about entertainment, a symposium about net art. This "limit," can and probably should be very wide-ranging, of course.

From a channel perspective, however, it makes no sense to limit the information choices about net art - or modern art - to only those works in your collection, or exhibition, or region of the world. A channel-appropriate and channel-efficient "network museum" rather than providing visitors information choices primarily about what is owned, contained, or otherwise constrained by the museum, would be just as likely to send that visitor away to some other information source. Might the "network museum" be more like a portal than a shopping mall, with all that tortuous navigation to keep you inside as long as possible?

Tough choice.

Interactivity

This is such an overused term.

Piotr Szyhalski, who I think is a master artificer and a brilliant artist, is as a master of a kind of false - or at least circumscribed - interactivity. In a way this is what the interactivity of most online museums is like (only without the artistry). You can push buttons and get a response, but there is seldom a dynamic feedback loop. Simply put, the museum does not respond. While the Walker is not much different in this regard, there is one important sea change in museums. Traditionally, the release of information was just that - a kind of controlled release that was often treated like papal encyclicals, the reintroduction of extinct species into former habitat, or the propagation of a virus - a meme, we might say now - into the general population.

What database access does is at least allow for users to find out what they want to know, not just what the museum wants to tell them.

Although not a result of online database access, this is the principle at work in Fred Wilson's recent project for MOMA, "Road to Victory." Museums have always told stories, but there has not always been the opportunity to counter or play with them. Wilson researched the MOMA's archives for several years and then used the Web to juxtapose different stories the museum has told over the years.

In the first frame of the project, Wilson quotes A. Conger Goodyear from 1932:

"The permanent collection will not be unchangeable. It will have somewhat the same permanence a river has."

For Wilson, over time, MOMA had lost a certain social agenda, which it had originally intended. He wrote about the project:

"These archival photographs expose the museum's use of didactic material to persuade the public of its liberal point of view as well as its aesthetic ideas."

Interestingly, in the very same press release that quotes Wilson, the pr speak about the project demonstrates it exactly and, presumably, unwittingly.

"Fred Wilson's online project, Road to Victory (1999)--titled after the Museum's 1942 exhibition that included photographs of the United States at war--explores The Museum of Modern Art's memory of itself: namely, the institution's photographic archive. Constructing narratives through juxtapositions and connections between documentary images and text borrowed from the archive, Wilson reveals much of what, though visible, is not on display: the Museum's visitors, staff, exhibition graphics, and wall texts."

Apparently, for them, or at least for official public consumption, the project was about mining the archives to display what is not on display - but things like graphics, not attidutes.

At the extreme of such interactivity is something like orang.orang, Open Radio Archive Network Group by. Basically, anyone who wants can get an ftp account and upload whatever she wants. The only control is a kind of "social filter," as Sara Diamond once described it. Yet this kind of unfiltered - that is, only socially filtered - database is anathema to most museums, which pride themselves on providing authoritative information.

One of the things that most museums have discovered, however, is that their authoritative information, so painstakingly gathered and vetted, is only a small fraction of what most people are interested in. Generaly, it's not surprising. Too often, it does not get beyond a repository of the given. I believe that it will be necessary for the "network museum" to create parallel and/or commingled databases and information resources that are truly two-way - interactive. Until then, we will continue to be citadels of information, not communities of co-learners. After then, who knows what may happen, what may be possible.

Connectivity

In many ways, this may seem like the core of any "network museum," since by network, I mean the global embrace, as both McLuhan and Roy Ascott have termed it, of telematic connections. In terms of connectivity, think of the issue as Sun Microsystems versus Microsoft. Microsoft owns the desktop, and up to now the company has prospered on the idea of a computer and its software on everyone's desktop. Similarly, museums own the art, and the museums with the best collections, by and large, dominate the market for cultural activity. With a network-centric model, it doesn't necessarily matter where something - whether it's an os or an application or some information - physically resides. The network connects them, and what becomes important are the relationships not the ownership.

This is a simplification, of course, but museums traditionally define themselves to a significant extent by what they own. If you look at this issue from the perspective of the visitor, they probably wouldn't make a special visit to the Walker to see its one Jackson Pollack drawing. On the other hand, the new Kazuo Shirago painting provides a context for his work that you might not find elsewhere.

This issue of links gets confused, of course, with paintings. You really have to stand in front of a Pollock to see it. But with network-based art - with net art - what does it matter what server hosts the bit stream you browse? And for that matter, why should presentation of the knowledge that a museum's staff has be limited to what it owns? It isn't, of course, but you seldom see museum websites that present a history of Abstract Expressionism much beyond their own collection.

The "network museum" will be about the passionate points of view it can connect up, not, primarily, what it owns.

Computability

Computability, of course, is Alan Turing's definition of the universal box, which we have come to know as the computer, but which he called the language machine. The computer is unique, among media, in its ability to understand and act upon symbolic instruction sets algorithmically. Alan Kay puts it this way:

"The hardest thing talking about computers is that things aren't always what they seem. You can do things with a computer for a long time without actually touching their essence, because they are such chameleons: they spend most of their time imitating other media, like paper, television, cartoons, movies. Most people who have used the computer have never touched what it is actually about. What's inside it is not esotric in the way quantum mechanics is esoteric. Almost everyone can learn to drive a car, to some extent, in about half an hour. But I have never found a way of explaining in a satisfactory manner what the music of a computer is in about half an hour. So I have to make an analogy. The most important thing to understand about the computer is that if it were a book, then it is a book that can dynamically read and write itself. Its static content is the same as paper. The computer contains just abstract markings, from which you can fashion anything--the symbols for language, any mathematics, any pictures. But that's too atomic a way of looking at it. Another way of looking at it is that much of its dynamic content is descriptions of media. It is a language machine that deals with things that are like sentences, and can not only move those sentences around and write them, but also read and write them. In a fairly open-ended way. It's a whole new way to deal with relationships between ideas."

Two of my favorite examples of computable net art include Simon Biggs's Great Wall of China, which responds to cursor movement to dynamically rewrite Kafka's story "Great Wall of China," and Paul Vanouse's interactive movies, Consensual Fantasy Engine and, most recently, Terminal Time, which, essentially, use algorithmic functions to respond to audience input and generate on the fly movies of, respectively, the O.J. Simpson trial in popular movie scenes and the history of the last 1,000 years.

What would an algorithmic museum look like? Part of it would be the ability to generate narratives - or at least compelling experiences- - out of our databases of facts and information. Having written about this in several papers, I will not go into the idea of procedural authorship tonight. Rather, I think there is a simpler and more fundamental way of thinking about computability, and that is process.

Ken Perlin's Wide World Web is a fairly simple java applet, which dynamically generates something suspiciously earth-like. Every time you launch this applet, it is slightly different, yet it is exactly what he intended. He created the software, which is simply an instruction set, which creates something specifically unpredictable but generally intended.

In Mark Napier's new (c)bots project and Andy Deck's Icontext, to this element of computability is added interactivity. For both projects, the "artist" creates an environment, essentially, which is rule bound but generates unpredictable results based on specific user (inter)actions.

And in their joint project, Graphic Jam, to computability and interactivity, they add the element of connectivity. Two or more people can be "making" something at the same time.

I think the "network museum" will be, increasingly, a platform for processes, both by artists and by audiences, as much as it is a purveyor of products. The more computable this platform, the more successful the museum.

Rhizomatic Culture: Hierarchy, Parasites and Complexity

On the network, nobody knows you're a virtual organization. In the physical world, organizations often tend to collaborate with their so-called peers. There is an implicit hierarchy. The Walker, for instance, was recently turned down for participation in an online project because, essentially, not enough people visit our building in Minneapolis. The relationship, however, between bricks and mortar and virtual seems tenuous at best, whether it is the example of Encyclopedia Britannica, which was initially bankrupted by the Encarta CD-ROM, Amazon.com, which is challenging Barnes & Noble as the largest bookstore in the universe, not to mention a few other industrial behemoths in terms of market capitalization, or, say jodi, who, I suspect have received significantly more online visits than the combined museum sites of all the curators who have done a studio visit with them. On the network, nobody knows you're a virtual organization. In the physical world, organizations often tend to collaborate with their so-called peers. There is an implicit hierarchy. The Walker, for instance, was recently turned down for participation in an online project because, essentially, not enough people visit our building in Minneapolis. The relationship, however, between bricks and mortar and virtual seems tenuous at best, whether it is the example of Encyclopedia Britannica, which was initially bankrupted by the Encarta CD-ROM, Amazon.com, which is challenging Barnes & Noble as the largest bookstore in the universe, not to mention a few other industrial behemoths in terms of market capitalization, or, say jodi, who, I suspect have received significantly more online visits than the combined museum sites of all the curators who have done a studio visit with them.

In a networked environment one map we use, as Dominguez said, is the idea of the rhizome, which has a horizontal, anti-hierarchical architecture. The "network museum" is a node, not a nexus or pinnacle - or nadir, for that matter.

One way to think of this lack of centralization, the decentralized interdependence of the rhizome, is complexity theory. As Mitchel Resnick, a professor in the Epistemology group at MIT Media Lab puts it, numerous individuals, whether they are birds in a flock or ants in a colony, by executing very simple "instructions," can give rise to very complex group behaviors.

Of course, as artists and creative types, we are especially sensitive, whether it is through the writings of Kafka or Foucault, the photographs of Brazilian gold mining by Sebastiao Salgado, or, simply, 4th grade science class, to these metaphors for capitalistic serfdom and the erasure of the individual.

Resnick's point is the opposite. As a society, we are too prone to reifying a centralized mind, a controlling or leading intelligence, when counterintuitively, much of the world works differently."

If increased "equality" seems too Pollyanna a way to understand the network, another conceptual map is the host-parasite relationship. Lisa Jevbratt, a member of the artist group C5, has said about her collaborative filtering Stillman Project:

"The Web offers and begs for new ways of discussing art. Thinking about art by playing with an Inviter/Host-Invitee/Guest-Noninvitee/Parasite continuum seems more appropriate than describing different roles and interpretations along an author-reader continuum. When I work on a project like this, the play between it being a parasite, a guest, and a host is what makes it interesting in terms of its ontological status as art. A parasite wants its host to be functioning well so that it can be "carried" and fed. A parasitic system also wants to understand its host system in order to get the most out of it."

If nothing else, the "network museum" could be a good host.

A Safe Place for Unsafe Ideas

The Walker sometimes describes one of its roles as a safe place for unsafe ideas. Sometimes this is an action such as the purchase of a Chris Offilli painting for the permanent collection soon after the Brooklyn Museum controversy, with a strongly-worded statement of support for his work. Sometimes it simply means having an installation crew that is tireless in support of what are sometimes known as artists' whims.

This is an ideal, of course, and I would never claim its attainment, but it seems to me that in an increasingly privatized and commercialized Internet space, the "network museum" could be a kind of safe place for work that is both unpopular in terms of its politics or unpopular in terms of public interest vis-a-vis, say, dancing hamsters or dancing babies.

Similarly, while in one sense it is relatively easy to get server space and to administer your own server, etc., it can become a burdensome chore or it can be subject to the whim of an ISP who may decide that the complaint about nudity on your site - or whatever - while legally protected, is just not worth the hassle and decide to shut your server down. I realize I am on tenuous ground here, of course, but in my ideal world, a "network museum" that was willing and able to provide this kind of infrastructure support with some modicum of backbone, so to speak, could be an invaluable role.

The Network Museum as Wonder Chamber

What else might characterize the network museum?

In his provocative and seminal essay, "Is there love in the telematic embrace?" Roy Ascott writes:

"In the telematization of the creative process, the roles of artist and viewer, designer and consumer, become diffused; the polarities of maker and user become destabilized. This will lead ultimately, no doubt, to changes in status, description, and use of cultural institutions: a redescription (and revitalization, perhaps) of the academy, museum, gallery, archive, workshop, and studio. A fusion of art, science, technology, education, and entertainment into a telematic fabric of learning and creativity can be foreseen."

Ascott is extrapolating a kind of cybernetic feedback loop, in which artistic network practice will inevitably and indelibly influence future institutional practice. I fervently agree with this, although resistance can be entrenched, and pro-activity on the part of institutions is important.

In this regard, I keep returning to a talk that the media historian Friedrich Kittler gave in Barcelona in the mid-90s, entitled "Museums on the Digital Frontier." "Frontier" is, of course, another one of those maps that Dominguez refers to, and Kittler's talk was intentionally speculative and not a blueprint per se for the "network museum." In it, he raised some important issues about whether the database, generically speaking, might not be a way to get back to the idea of the "wonder chamber," before the specialization of the modern museum, circa 1800, when, as Kittler quotes Paul Valery, "sculpture and painting lost their mother, architecture, to death. Like orphans, the two arts wandered homeless through the world, until the museum offered them sanctuary."

I will not try and represent his talk here in detail, but would like to suggest a line of flight that interests me a great deal. Kittler wrote:

"With the rise of the museum as a separate sphere, "technological knowledge was no longer the goal or result of a collection; it now became both its necessary and covert condition."

In other words, whereas the wonder chamber included not only artworks, these were accompanied by marvels of science, technology, and nature. In the modern museum, circa 1800, not only was the display of this technological knowledge banished elsewhere, but it was naturalized and effectively made covert, a technique of display not an object of knowledge. The result, according to Kittler, is that "the age of wonder chambers has not returned. Instead, side by side with the art museums, countless special technological collections have sprung up." Can the "network museum" be that wonder chamber?

If, for instance, the "network museum" can begin to render irrelevant the walls between domains - between gallery and library and archive - it can also subvert the hierarchy of gatekeeper and supplicant. I don't think this is an either/or issue. It's not that curators, educators and others should not present their point of view. But their's is not the only point of view. It is not to be conflated with the institution, with history. Access to all the information by anyone is a critical facilitation of the network museum, if it is to prosper in an age of mass customization and interactive transactionality. Kittler wrote:

"What looms ahead or rather what has to be done is the reprise of the wonder chambers. Johann Valentin Andrea, the founder of the Rosicrucians, once advocated an archive that would include not only artworks, tools, and instruments, but also their technical drawings. Under today's high-tech conditions we have no choice but to start such an archive or endorse millions of anonymous ways of dying."

I think it is significant that Kittler identifies museum business-as-usual, essentially, as deadly for the museum itself. Certainly, to the extent that "museumification" is a kind of classification, it is no wonder that many artists are skeptical, at best, of the mausoleumizing of the vibrant net culture they have been creating and participating in. To a large extent, "new media" is an activity, not always a product, and, to paraphrase Barnett Newman, databases are for artists what ornithology is for birds.

Yet, in the digital age, institutions cannot afford not to at least try and understand, present, collect, and preserve contemporary artistic activities.

A Modest Proposal: The 24 x 7 x 10 museum

How do we get from here to there? Or, is there any there there?

My modest proposal is as follows. A 24 x 7 x 10 "network museum." Being near the heart of Silicon Valley, I do not need to explain the 24 hour-a-day, 7 day-a-week work week. The museum needs to go 24/7. But what is this third dimension of 10?

Well, being near the heart of Silicon Valley, we need an exit strategy.

We all come to "new media" from many different perspectives, whether it is video-based media arts, computer science, literature, conceptual art, education, publishing, etc. I come to the table with a background in photography, so that is my example.

Photography is useful, of course, because it epitomized the endless debate of is it art or is it mechanical? Is all this network activity art or is it just technology? And important issues about the status of art and museums and archives and libraries have been raised by Douglas Crimp and others by the classification problems of books of photographs in the New York Public Library. But I would like to make a simpler, more instrumentalist analogy.

Very simply put, when ICP, the International Center of Photography in New York, was founded not that long ago by Cornell Capa and others, it brought a clear sense of focus and invaluable energy to the field of photography in general and of documentary photography in particular. It was able to do on an ongoing basis, what museums and other institutions only presented sporadically and more often than not without a complex, historical context. ICP served a galvanizing function, I would argue.

ICP continues to present important exhibitions - or not, depending on your point of view - and it serves a dedicated constituency faithfully. Yet, its need to exist - as opposed to its desire and ability to exist - seems less critical. Even problematic. A kind of photography ghetto in uneasy relationship to the art neighborhood. At this point in time, how much do we want to think about photographic practice separate from art practice or documentary practice or communications in general?

Net art and technology-based art, it seems to me, is one of the most dynamic and potentially exciting arenas of creative endeavor existing today and increasingly so in the near future. Yet, as with photography early on, institutional response, especially in North America, is tepid, episodic, secondary, decontextualized, minor. Even as one looks hopefully at the confluence of a Benjamin Weil, Aaron Betsky, Peter Samis, and David Ross at a museum such as SFMOMA in such a fertile crescent of activity as the Bay Area, perhaps an autonomous "network museum" is needed. One built from the ether down, not as an extension beholden to existing agenda and inalterable histories.

Yet, inevitably, even if successful - or perhaps especially if successful - such an autonomous "network museum" would become a defender of the status quo and its own history rather than a protagonist for the future. But what if the "network museum" were created with the express intention that it would be dissolved after 10 years and its invaluable collections, archives, and library dispersed appropriately for the time. Who knows, in this time of too little support for such artists, who are often collected and exhibited with little or no monetary compensation, perhaps they receive a percentage of any future buyout and the potential of receiving a future 10x dollars is a reasonable trade-off for a present x dollars.

Hal Foster ends "The Archive without Museums": "Like essentialism, autonomy is a bad word, but it may not be a bad strategy: call it strategic autonomy."

Perhaps the 24 x 7 x 10 "network museum" can be such a strategic autonomy.

|